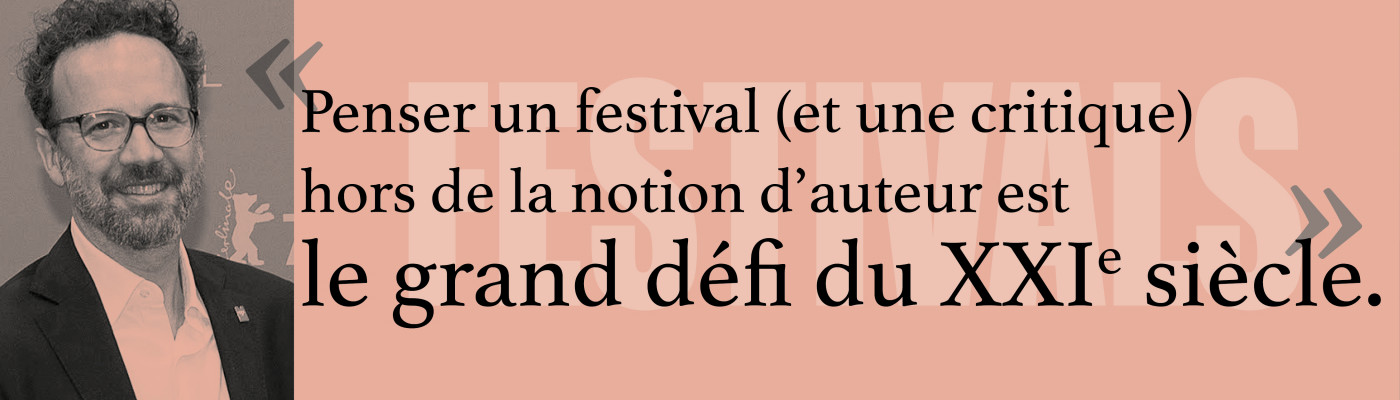

CARLO CHATRIAN (Italy)

Artistic Director of the Berlinale (Germany)

Pour consulter cet article en français, veuillez vous rendre à ce lien.

Festivals and critics

To Pierre and Jean, the two poles of the world I grew up in

Like many of my colleagues, I was a film critic before I joined the world of festivals. It’s hard to point out exactly what it was in that experience that influences my current work as a programmer. However, I know that even now, the simple act of scribbling notes, jotting down ideas and thoughts, expressing doubts or enthusiasm during a phone call or by email is part and parcel of my work. This selection process allows me not so much to reconsider the films but to question my own tastes, which can be very volatile and are subject to changing fashions, trends and moods.

Of course, sometimes films impose themselves and require an immediate response. And yet, I’ve come to understand that widening my own perspective, confronting my own thoughts with those of others can offer up many surprises. Basically, it’s important to look out for the emotions, thoughts and reactions that a film provokes.

There are many ways in which to exercise your role as a critic: personally, I’ve never considered it as a channel for self-assertion. I grew up in a border region and more than the feeling of belonging to a specific community, language or parish, it was the longing to see what lay on the other side of the mountains that drove me. I saw film criticism as a mirror for a world that was split in two as a result of the Second World War, a world with the good guys on one side and the bad guys on the other, where you have to pick your side, draw your weapons, aim for the most visible targets and fire… Where filmmakers are divided up into those we must defend and those we must tear apart at all costs… All of which wore me out.

So I have to say that festivals allowed me to move away from this dynamic. Watching films back to back, flitting from a film by an established director to one whose title is the only information I have, listening to the suggestions of crowds that are each time different, larger and more heterogeneous than those we encounter on a daily basis… all this gives our analyses a wider perspective, less fenced in by our own subjective judgement and better predisposed to question our own principles. Festivals, to me, are places of openness, where the question of mise en scène takes on a multitude of expressions.

I started going to festivals as a critic at roughly the same time I discovered the written works of Serge Daney, which presented to me an important counterview. As a bit of a trailblazer for a world that no longer seemed to have insurmountable barriers, he “flitted” from one subject to another, from one world to another, discovering new approaches to cinematography, championing new voices, bringing together the established and the new, the noble and the popular, the high and the low. His texts are an invitation to travel, through time, through space and with the mind.

We often reduce festivals to the act of selecting when what I find interesting, what gives me the most pleasure is programming: creating hypotheses that connect the films together and form the building blocks of the festival. A bit like in editing, one must avoid lazy connections and underestimating the intelligence of audience members by leaving certain gaps that they can then fill.

I have been lucky enough to work in non-specialist festivals, which has allowed me to pair old films with new, mainstream with arthouse, documentary with fiction. Whilst film criticism sharpens the vision, festivals open doors. We must of course maintain some sort of common thread and avoid programming that turns eclecticism into chaos but we should really be open to clashes. Let’s not forget that out of conflict comes great passion. Does a festival represent a particular vision of the world? Or is it rather a house that can accommodate many worlds? As far as I’m concerned, there is no right answer. There are answers that are in turn the result of long-term work and unexpected opportunities. I often find myself thinking in dialectical terms between the need to establish a particular and coherent vision for a programme and the desire to create one that’s open enough for each and every audience member to find their place.

The issue of the audience is often brought up in festivals but I feel that using this term - the audience - is actually misleading. The audience is always on the other side: once the selection is made, they will be the judge. And often, the response incites us to be more audacious. Then again, it’s true that each festival creates unique conditions and treats its audience to occasional tours de force. With this in mind, I tend to think of criticism as the result of an elective act. We write to respond to the emotions, feelings and questions that a film arouses. In festivals, we also form our selection based on the fact a film has spoken to us, that what it said struck a chord and still resonates and that we’d like to share that with everyone. There are many differences between selection and election but throughout the years, festivals have progressively abandoned the principle by which films should reach them like a diplomatic delegation, and have started actively looking for films as opposed to just selecting them.

Festivals, like film criticism, enable and encourage a direct relationship with creators. Meeting filmmakers is an essential part of my work, and a real pleasure. At the same time, by developing those connections, we run the risk of losing that distance that regulates all professional relationships. Distinguishing between the person and the filmmaker can become near impossible and yet this is something that we must do. Criticism created and sustained the concept of auteur. I won’t go into its origins but it’s worth bearing in mind that this concept has proven both efficient and flexible. The result is that today auteur has become synonymous with filmmaker, in a positive sense. Festivals especially can’t do without it even when their target is elsewhere, as if the festival’s selection is always de facto “auteur cinema”. Whilst for critics, an “auteur” is someone with whom we establish an affectionate rapport, who we are prepared to defend even when their voice doesn’t resonate with everyone, for festivals, “auteur” implies safe bet and by extension ticket sales. Thankfully, reality is much more complex than that. It remains true that moving away from an intrinsic link between festivals (and criticism) and “auteurs” will be one the 21st century’s great challenges.

The fact that festivals today are subjected to a degree of homologation is partly the result of a shrinking world where cultural and linguistic distinctions have lost some of their purity, and partly the result of film critics imposing the concept of “auteur” as a unique alternative to commercial success.

It would be naive to end this letter without mentioning the growing place the market occupies. I’ve mentioned a few times the concept of “openness” here in regards to festivals, the will to make space for new work. The Semaine de la Critique who, with its selection of first and second films is the perfect example of that, is also coming up against the increasing normalisation of tastes, which is ubiquitous on the market. Festivals are very complex machines. They have been able to grow in scope and power because the market understood that they give independent cinema the showcase the market itself cannot provide. Both critics and festivals aim to differentiate between certain features: their independence from the logic of profit gives films a unique position. Selection and awards are the ultimate mark of quality. Notwithstanding, festivals today allow more and more films to exist. They don't just certify their values, they ensure their survival. (The exceptional contractions experienced this year attest to this). It seems to me that the growth of festivals has taken some of the power away from critics.

In the age of social media, critics sometimes give up on the idea of developing discourses and opt for just saying things, thus making themselves vulnerable to the power of the market, to what the “public” wants or would like to read and hear.

Although on the one hand we can witness a joint action by the press, certain institutions and unions to better tackle some of the weaknesses of the “cinema system” and the generational flaws of a culture that’s thankfully finally starting to question some preconceptions, on the other, it is sad to see how discourses are often reduced to the inclusion/exclusion polarity, which for me is very much a market-based dynamic. In this context, the role of independent and autonomous critics, who don’t just anticipate and judge the choices made by festivals, is vital. We are not lacking in critics but in a system that allows critics to really fulfil their remit. In a world where we are always rushing from place to place instead of travelling, trying to cram in as many films as possible, the work of critics can act as a powerful remedy. A bit like oxygen for someone who’s out of breath.

Carlo Chatrian